A Personal Face to the Father of Modern Zionism

By Fern Sidman

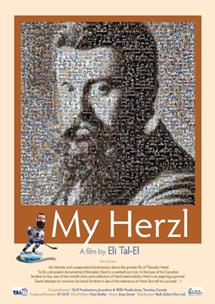

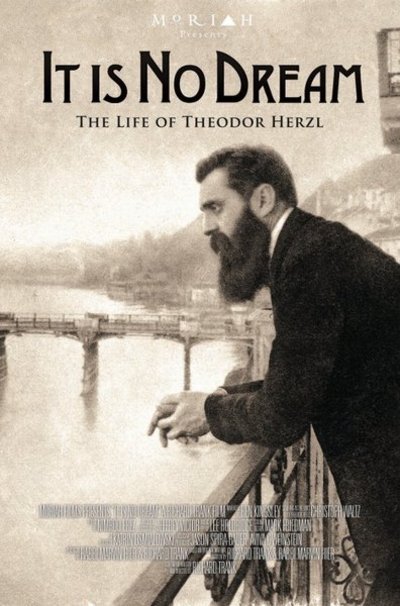

In this seminal biodoc on the life and arduous struggles of the progenitor of the establishment of the modern Jewish state of Israel, Academy Award-winning director Richard Trank (“The Long Way Home”) presents a compelling and spellbinding portrait of Theodor Herzl; a man who was often shunted aside or patently misunderstood in the annals of history. Produced by Moriah Films, in association with the Simon Wiesenthal Center film department, “It Is No Dream: The Life of Theodor Herzl” puts a personal face, hitherto unknown, on the vicissitudes that Herzl endured in his relatively short, but historically impactful life.

Narrated by actors Ben Kingsley and Christoph Waltz (of “Inglorious Bastards”) Herzl’s angst and unadulterated passion leaps forth from the screen and punctuates our psyches. Director Trank liberally utilizes rarely seen black and white photos, archival articles, and somewhat eerie-sounding music, in this meticulously researched film, which would impress even the foremost scholars of Jewish history.

Herzl as a child with mother, Janet and sister, Pauline

Born in Hungary in 1860 to Orthodox Jewish parents, Herzl was the archetypal cosmopolitan Jew; a victim of rampant assimilation that marked this era in history. A child prodigy of sorts, at the tender age of eight, Herzl mastered the works of Schiller and Goethe in the original German when his parents moved to Austria where he was raised. It was highly improbable that this young man, a Jew in name only, who was “confirmed” rather than being bar mitzvahed at 13 and who held aspirations for a career in law, would ever entertain the notion of leading a one-man crusade for independent Jewish statehood that captured the imagination of the world.

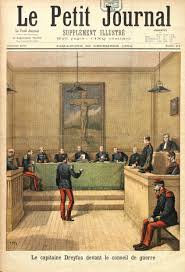

Focusing his creative energies on writing, Herzl found his niche as a talented playwright, author of novellas and short stories, and soon assumed the role as a full-time journalist for the Austrian newspaper Neue Freie Presse. Assigned to their Paris bureau as a foreign correspondent in 1894, it was there that Herzl’s prescience ignited when he covered the infamous trial of Alfred Dreyfus, a French Jewish military officer, who was brought to trial on trumped up charges of treason.

The age-old strains of virulent anti-Semitism that had occasionally erupted but always simmered under the surface in France and throughout Europe exploded exponentially during the duration of the trial.

Witnessing the French populace, united in hatred, and screaming, “Death to the Jew,” Herzl quickly came to the horrifying realization that Dreyfus’s trial, conviction, degradation and humiliation would translate into existential perils for the Jews of Europe. Intensely pondering the Jewish question, Herzl’s epiphany took shape when he became a fiery advocate for a Jewish return to their ancestral homeland of Palestine in order to flee an endemic anti-Semitism that would have catastrophic consequences.

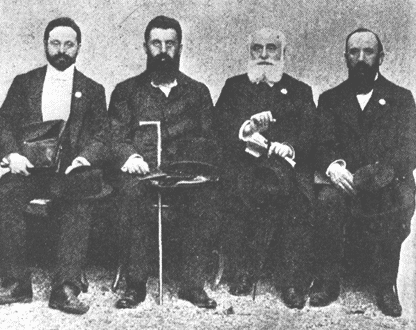

Enlisting the help of Jewish intellectuals throughout Europe, including Max Nordau and Sigmund Freud, the lion’s share of support for Herzl’s dream came from the grassroots movement of Jews from Poland, Russia and other places in Eastern Europe, who had personally felt the brutal lash of anti-Semitism. Outlining his plan in the 1895 work titled “The Jewish State,” Herzl’s trajectory was clear as this transformative process ultimately led him to devote himself exclusively to the completion of his quest.

Max Bodenheimer, Theodor Herzl, Max Nordau and David Wolffsohn

Offering unique insights into Herzl’s life is Robert S. Wistrich, the Neuberger Chair in Modern Jewish History at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem and a world expert in the field of anti-Semitism. Others, such as Israeli president Shimon Peres and Swiss producer Arthur Cohn, are also featured as they articulate Herzl’s critical role in the founding of the modern Jewish state. Buttressing the undulating narrative of Herzl’s complicated mission is the poignant narration of Christoph Waltz as the voice of the father of Zionism. The viewer cannot help but to be exceptionally moved by Herzl’s pain, frustration, anger, and eventual hope, as his words sear our soul. Herzl’s own wife vehemently resented her husband’s cause célèbre and asked, “What happened to the man about town?”

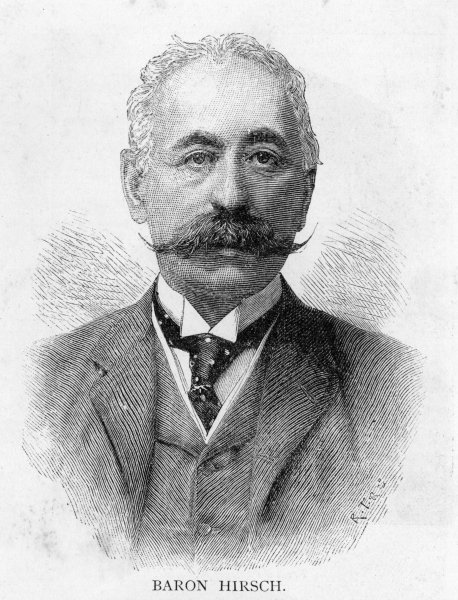

Herzl was keenly cognizant that massive funding was essential to ensuring that his plan for Jewish statehood would come to fruition, so he attempted to solicit commitments from such financiers as French railroad tycoon and philanthropist Baron Moritz de Hirsch, who agreed to meet with Herzl in Paris.

Ultimately, doors were figuratively slammed in his face by de Hirsch and the Rothschilds, who were overtly circumspect of what they perceived as his seemingly vague and unrealistic notions. Newsreel footage of Herzl’s one and only trip to Palestine left the viewer sharing Herzl’s melancholia over the abject poverty and destitution that he witnessed amongst the Jewish population at that time.

As time passed, significant percentages of Jews, both religious and secular alike, would come to shower Herzl with well-deserved plaudits, and they even bestowed a degree of reverence on him as a harbinger of the Jewish redemption from exile. Totally immersed in his mission, Herzl met with kings, heads of state, prime ministers, ambassadors, government ministers and even the pontiff in Rome in order to obtain legitimate rights to the land of Israel and to facilitate Jewish immigration there.

Having no other option, Herzl used his own money to set up his infrastructure, which included the launching of a Zionist newspaper, the creation of the World Zionist Organization, and the first World Zionist Congress, held in Basel, Switzerland in 1897. Feeling a terrible sense of urgency for his people and having no other viable recourse, Herzl took a great risk when he proffered the idea of establishing a Jewish state in Uganda to the Congress delegates. He was met with visceral acrimony along with a litany of ad hominem attacks by such iconic Zionist leaders as Chaim Weizman and others like him.

Deeply perturbed by the lack of appreciation from his contemporaries, Herzl nonetheless girded his loins and changed his tune. He now would not settle for any other land for the Jewish nation other than the biblical land of Israel.

While Herzl remains a controversial figure to this very day (especially in religious Jewish circles) for his adamant secularism, it is noteworthy to mention that the film reveals that on the Shabbat prior to the First Zionist Congress, Herzl joined the delegation at an Orthodox synagogue for services. When called up to the Torah, without being prompted, Herzl recited the blessing in perfect Hebrew and with sincere dedication.

Herzl’s final work was a novel titled “Altneuland” (Old New Land), which gloriously envisaged a thriving and prosperous autonomous Jewish homeland in ancient Israel. It was in these pages that Herzl penned the words that he will eternally be remembered for: “Im tirtzu ain zo aggada” (“If you will it, it is no dream”).

Kudos to Moriah Films, director Richard Trank and Rabbi Marvin Hier of the Simon Wiesenthal Center for preserving the legacy of Theodor Herzl on film for generations to come.

No doubt, this pulsating and highly original documentary will leave us moved by the unwavering dedication of one man’s vision that changed the course of Jewish history.

Fern Sidman is the New York correspondent for the Arutz Sheva (Israel National News) Web site and a staff writer for The Jewish Voice newspaper. Her articles frequently appear in a number of Jewish newspapers, magazines and other publications throughout the US.