Purim: When Hebrews Became Jews

By Rabbi Lazer Gurkow

The Jews

Today we are known as Jews, but in the Torah we were known as Hebrews and Israelites. Who are we really, Hebrews, Israelites or Jews? The more I think about it, the more I feel an identity crisis looming.

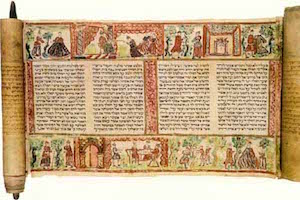

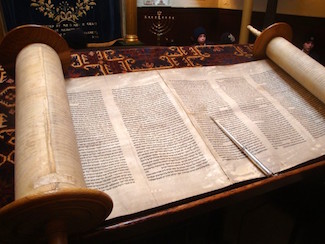

It might surprise some to know that the first time our people were known as Jews was during the Purim saga. Mordecai is introduced in the book of Esther, as the Yehudi – the Jew. What most people don’t realize is that Mordecai invented this name or, at the very least, popularized it.

Mordecai’s change caught on and the new name stuck. Today we are known almost exclusively as Jews; with few archaic exceptions, we are never described as Hebrews or Israelites. It was a spectacularly successful effort, but why did he do it? What was wrong with our first name?

A Little Background

The story of Purim occurred in 358 BCE. The Babylonians, who, in 350 BCE sacked and destroyed the Temple, forced the exile of our people to Babylon. This exile was foretold by our prophets and was slated to last for only seventy years. Indeed, Jews returned to Israel and rebuilt their temple in 420 BCE.

Cylinder seal and inscription of Cyrus the Great from Babylon

When Cyrus II of Persia defeated the mighty Babylonian empire, he was supported by the Hebrews. (1) Under Cyrus the Hebrews flourished; they profited mightily from their support of Cyrus the Great and many were appointed to powerful posts in reward. Mingling with their Persian neighbors, the Hebrews gradually abandoned their faith and traditions; assimilating into the larger Persian culture.

When Achashverosh acceded to the Persian throne, Hebrews continued to enjoy unprecedented freedoms and opportunities. Achashverosh led many military campaigns against his neighbors, each supported by the Hebrews, who fought in his ranks and supplied his armies.

In 368 BCE, having returned from an extensive and brutal war in which his empire was successfully expanded, Achasverosh, flush with victory over 127 provinces, threw a ball to thank his allies and supporters. The Hebrews, entrenched in the highest echelons of Persian society, commerce, military and government, were invited as equals to this party.

Mordecai, himself a powerful minister, warned his people against accepting this invitation arguing that the party would be a perfect opportunity to assimilate wholly and seamlessly into Persia. He reminded them that the seventy year exile was nearly over; the prophesied return to Israel and rebuilding of the temple was a mere eighteen years away. Surely they would not discard their destiny for the false promise of power, acceptance and greed.

The Hebrews, enormously wealthy from their association with Persia and drunk with their own successes, disdained the coming redemption, rejected Mordecai’s advice and derided the Jewish tradition. They no longer felt a need for G-d. Ingratiated with the wealthy and powerful Persians, they were now protected from harm and perfectly willing to discard their forefathers’ faith.

The Name Change

For years the name Hebrew was associated with our patriarch Abraham, the Hebrew. Our people proudly bore this name, proclaiming before the world that they were heirs to Abraham’s faith. Just as he followed G-d despite challenges, dangers, temptations and obstacles, so did his children. The very name Hebrew connoted a fierce loyalty to G-d.

Over time a new generation arose; a secular Hebrew nation that rejected Abrahamic faith and tradition. They saw themselves as a nation among nations, a political entity that was naturally suited to form alliances with neighboring tribes and perfectly willing to absorb new teachings and traditions. The name Hebrew was stripped of holiness and bore no resemblance to its original meaning. (3)

Mordecai and those Jews who had remained loyal to Torah had had enough of this corruption. Painful as it was to reject a name they had once cherished and revered, they chose to adopt the nomenclature Yehudi – Jew. Yehudi means to acknowledge the truth of G-d and to commit above all to His Torah. This fierce loyalty, dictated by our quintessential connection to G-d, is intrinsic to the Jew.

Jews were now divided into two distinct groups; secular Hebrews and religious Jews. Mordecai kept warning against reliance on wealth and power, but the secular Hebrews continued to deride him.

Haman

Haman was a poor barber, who chanced upon an enormous treasure and parlayed his newfound wealth into a powerful position in the royal court. He was a cunning man, who strategically injected large sums of money into the right coffers and thus ingratiated himself with the King.

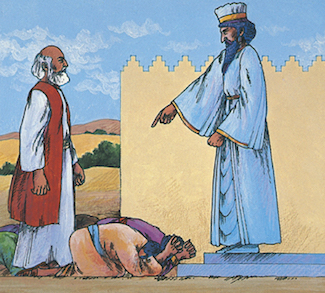

Rising from humble origins, Haman craved respect. The king obliged him and ordered all to bow before him. The secular Hebrews, who were friendly with Haman, eagerly bowed to him and benefited from his largess. But Mordecai refused to bow. Haman was enraged, but also mystified. He asked his Hebrew friends, why Mordecai, a successful and powerful politician, would risk his post by refusing to bow.

The Hebrews explained that Mordecai wasn’t a Hebrew; he was in fact a Jew. Jews, they explained, were anachronistic throwbacks to the dark ages, who refused to embrace Persian society and, who harbor foolish hopes for an eventual redemption.

Haman had heard enough and flew into a rage against Mordecai and his people. He campaigned for several years against the Jews and finally, having promised Achashverosh ten-thousand silver pieces, he secured permission to annihilate them. The date for annihilation was set to Adar 13, 356 BCE; a mere six years before the seventy year exile was slated to end.

Though Haman tolerated the Hebrews, his sons and henchmen targeted them too. Just as Mordecai had predicted, the wealthy Hebrews suddenly found themselves vulnerable despite their former power. At this point they rediscovered their faith and quintessential connection with G-d. They joined Mordecai in his prayers and began to attend his lectures. They stood fast to their heritage throughout this time despite the danger to life and limb. (4)

Conclusion

The story had a happy ending as we all know. Esther changed the king’s heart, Haman and his sons were hung and the Jews secured the right to defend themselves in war. Not a single Jew died in battle and indeed, six years later the Jews returned to Israel and rebuilt the Temple.

The nomenclature Jew remained. It stands for much more than nationality and culture. It stands for more than tradition and history. It stands for more than a homeland and economy. It stands for our eternal connection with G-d, our undying loyalty to the Torah and for the immortality of our people. The nation that survived Haman and the nation that, G-d willing, will for ever continue to survive. (5)

Footnotes

- Secular historians date the Persian victory over Babylon to 539 BCE. Our traditions teach us that this victory occurred more than a century later, shortly after the Jewish exile to Babylon in 420 BCE.

- This change is also evidenced in Jonah’s words (Jonah 1; 9) And He said to them: I am a Hebrew and I fear G-d, the Lord of the heavens. That he had to add the fact of his allegiance to G-d even after having identified himself as a Hebrew speaks volumes about what the name otherwise evinced in his day.

- For the section on Haman see Babylonian Talmud, Megilah 12b and 16a

- This essay is based on Likutei Diburim, Purim 5701.

Rabbi Eliezer (Lazer) Gurkow, currently serving as rabbi of congregation Beth Tefilah in London, Ontario, is a well-known speaker and writer on Torah issues and current affairs.