Serbian Warrior, Zionist Hero

By Michael Freund, The Jerusalem Post

December 17, 2013

The annals of Zionism, like those of any successful national liberation movement, are rife with heroes, individuals whose names and deeds continue to resonate generations after their passing.

Men such as Theodor Herzl, Ze’ev Jabotinsky and Chaim Weizmann pervade our collective historical consciousness; larger-than-life figures who shaped the course and contours of modern Jewish history.

But inevitably there are those whose contributions to the cause somehow get overshadowed despite the key role they played in the unfolding of events.

With this past anniversary of the 1917 Balfour Declaration, in which the British government reaffirmed the right of the Jewish people to renew their ancient Biblical homeland in the Land of Israel, this is a good opportunity to recall one such unsung Zionist hero who helped to spark a groundswell of international sympathy and support for the Declaration and its aims.

David Albala was an observant Sephardi Jew born in Belgrade, Serbia, in 1886. His father was a successful merchant and a committed Jew, and already as a high school student, young David was chosen as president of the local student Zionist society.

In 1905 he went to study medicine in Vienna, where he became even more involved with Zionist activities.

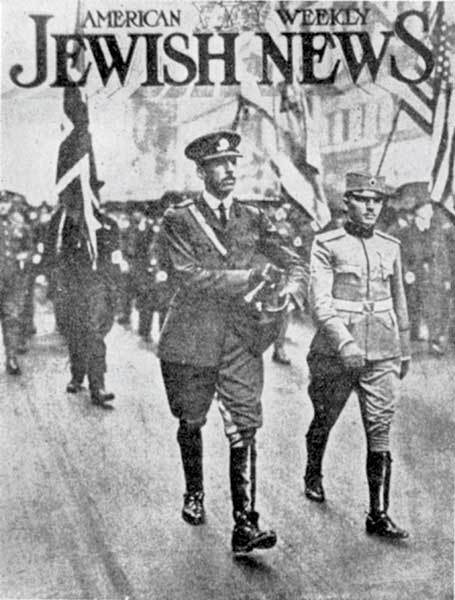

After he became a doctor in 1910, Albala returned to Serbia, joined the Serbian Royal Army, and proceeded to fight in the First and Second Balkan Wars as well as World War One, all in the space of five years.

He rose to the rank of captain, distinguishing himself on the battlefield and surviving a bout of typhus.

While recuperating from the disease at a British hospital in Cairo for four months, he learned fluent English by conversing with the nurses and fellow patients.

As a result, the young Serbian Jewish patriot was dispatched by the Serbian government to the United States, where he toured Jewish communities across the country to drum up their support. He met with luminaries such as Justice Louis Brandeis and gave interviews to the Jewish press.

Then, on November 2, 1917, the Balfour Declaration was issued, in which British Foreign Secretary Arthur James Balfour stated clearly and unequivocally that Britain’s leaders “view with favor the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavors to facilitate the achievement of this object.”

While Jews everywhere rejoiced, and the Arabs were furious, governments around the world remained silent. If the Balfour Declaration were to have a lasting impact, it was imperative that it garner widespread international backing.

And that is where Albala came to play a crucial part.

Utilizing his close relations with the Serbian leadership, he suggested that they declare their formal support for the Declaration and its goals.

Shortly thereafter, on December 27, 1917, Serbia did just that, becoming the first country in the world to openly endorse the Declaration.

In 1919, the Zionist Organization of America published a fascinating volume called The American War Congress and Zionism, a collection of responses to the Balfour Declaration by more than one hundred US senators and congressmen.

In addition, it also contained the statements of support that were issued by various governments around the world, including that of Serbia.

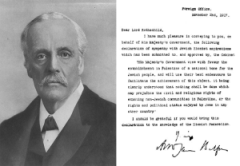

The letter, addressed to Captain Albala and signed by the Serbian representative in Washington Milenko Vesnic, is a highly emotive document and is worth quoting at length.

“I wish you to express to your Jewish brothers,” Vesnic wrote, “the sympathy of our Government and of our people for the just endeavor of resuscitating their beloved country in Palestine which will enable them to take their place in the future Society of Nations according to their numerous capacities and to their unquestioned right,” it said.

“We are sure,” the letter continued, “that this will not only be to their own interest, but at the same time to that of the whole of humanity.”

“You know, dear Captain Albala,” he added, “that there is no other nation in the world sympathizing with this plan more than Serbia.”

After noting that Serbians had also shed “bitter tears on the rivers of Babylon” when their country had been invaded and occupied, Vesnic went on to state, “How should we not participate in your clamors and sorrows lasting ages and generations, especially when our countrymen of your origin and religion have fought for their Serbian fatherland as well as the best of our soldiers?”

In closing, Vesnic wrote that, “It will be a sad thing for us to see any of our Jewish fellow-citizens leaving us to return to their promised land, but we shall console ourselves in the hope that they will stand as brothers and leave with us a good part of their hearts and that they will be the strongest tie between free Israel and Serbia.”

The Serbian letter marked the first time any government had referred to the yet-to-be-born Jewish state as “Israel,” presaging the name that would be adopted by the nascent republic three decades later.

More significantly, it broke the international ice, paving the way two months later for France and Italy to back the Balfour Declaration, followed shortly thereafter by Greece, Holland and others.

This would prove to be immensely important, because when the League of Nations, the precursor to the United Nations, approved the Mandate for Palestine in July 1922, it formally incorporated the Balfour Declaration, which essentially laid the conceptual groundwork for the establishment of the modern State of Israel.

And much of it was thanks to the efforts of David Albala, the Serbian Jewish war hero whose lasting achievements on and off the battlefield will one day, hopefully, receive their due.

In an interview with The American Jewish Chronicle in 1917, Albala related a personal story that is as relevant now as it was in those turbulent days.

After returning from his university studies in Vienna, he said, “I did not visit the synagogue as often as in the boyhood days before I departed for the Austrian capital.”

One day, after his father took him aside and expressed pained surprise at his behavior, Albala defended himself by asserting, “But I am a devoted Zionist.” To which his father replied, “Ah, my son, one must be a Jew as well as a Zionist.”

And to his dying day, Albala carried out his father’s charge, setting an example that we would all do well to emulate.

To read the full article, click here.