Something to Remember

By Gila Green

All I remember of my grandmother’s house was her doll collection. I was five and overweight from too much Kentucky Fried chicken, dripping with the honey they’d give you in those bite-sized plastic containers, and I was as shy as any fat kid in a foreign country.

I remember a room with low ceilings and walls that felt too close together, and an ancient woman, who covered her hair and neck with a night-blue scarf, opening the thin wooden doors to a closet which was filled with the dolls she had spent many years collecting. I cannot remember any specific doll; I see only a jumble of bright eyes and plastic grins of different shapes and sizes in neat, dusted rows.

My grandmother was pointing at the dolls and smiling down at me, and I hope I smiled back, but honest to God I don’t remember. I know that chances are I stood like my own young daughter often does when confronted with a stranger: shrugging a shoulder up to one ear, mouth ajar, eyes unnaturally wide. I hope not. I hope I made her smile that one and only time.

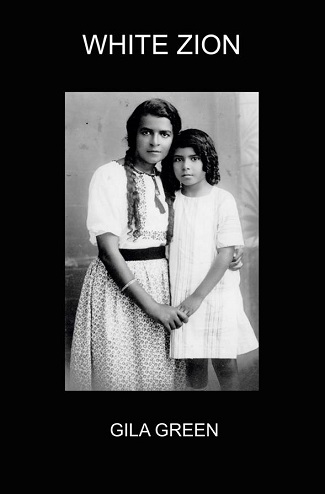

In my novel-in-stories White Zion my heroine, Miriam (Miri) Gil, is both haunted by and trying to tear herself away from memory. Though one of the major themes of White Zion is immigration and the fall-out from war, you could fill a drawer with the various sub-threads. One such sub-thread readers can easily tease out is coping with tragic memories and, in the case of this excerpt, coming face to face with the absence of any memories at all.

In Miri's case, as an adult, she discovers a photo album that offers a tiny glimpse into her paternal grandmother's life. She is aware that her grandmother, who was born in Ottoman Palestine, died when she was ten years old. She had always been told that her grandmother died accidentally, but now as an adult, she revisits this version of the story—at times unwillingly when she's trying to sleep.

REMEMBERING THE FORGOTTEN

This absent grandmother is named Nomi El-Karif. And Nomi's death has culpability splattered all over it. Adulthood means a depth of understanding that was previously blocked to Miri. Now she struggles to swallow the circumstances: her uncles were young, burdened with small children, unable to care for their absent-minded mother. Her father was an ocean away, so distant he may as well have been camping out on Mars. Or that's the way the story was always presented.

So, nobody had the peace of mind to consider deeply the consequences of placing a physically strong, sixty-two-year-old woman in an old-age home. There were empty stomachs to be filled, bills to be paid, and in her father's case, an ocean so wide, even his mind could not cross it.

The result?

Nomi, who wants nothing more than to return to her childhood home and has long forgotten that her parents are dead, flees the old-age home. For three months it is as though she never existed—until one day when her body is discovered in a forest by passing backpackers.

Though Miri must now reprocess this tragedy as an adult, ironically, there is not a line in the novel she begins with anything close to "Remember when?" Remember when grandmother was found dead in a ditch? is not a sentence she can approach. It is not something she can toss at her tight-lipped father or hold out to her icy mother. There is no one with whom she can share this absence of memory and because she cannot give what she doesn't have, the reader is not an option for her either.

Miriam's angry father never mentions his mother's death to her, possibly because he is himself unsure of what really happened. After all, who chose this old age home? Were references given or was it merely a convenient location? Who wasn't on duty that night when his mother escaped? These questions go unasked and are buried along with Nomi in a ditch in a Jerusalem forest.

THE ALBUM OF ALLEVIATION

There's no one on earth to clue Miri in, so she flips through a photo album that itself becomes a companion for her. It is through the album that she begins the process of healing, because the album is safe. She can ask all the questions she likes; she can flip back and forth to images of her young, radiant grandmother. Through the photo album, Miri remains faithful to the false memories she concocts on her own to soothe the absent ones. She cannot get enough of the would-have-been sunny afternoons and easy laughs every granddaughter craves. They are all there in the precious album Miri comes to prize.

THE BATTLE FOR MEMORY

It is precisely what she believes her grandmother would have said to her if she had only not plunged to her own death, that propels the plot forward, enables a new layer of false memories to replace the void in Miri's heart. When Miri admits how much she would have liked to have had another grandmother, instead of weighing herself down in grief, these imaginary memories yank her up out of her hopelessness and toward actualizing her strengths and finally, success.

The question for the reader is if it is believable that Miri has grown enough to stand her ground and resist the temptation to blame her uncles and aunts once more, or to take a stab at her father when her buoyancy passes?

Or can Miri see the larger picture for good now that she has processed this loss? Can the reader imagine a higher resolution Miriam Gil by the end of White Zion? A heroine who fingerprints a firm protective layer over her grandmother's ugly death as food for animals at the base of a cliff. Could Miriam Gil preserve what's lifegiving about the familial database she does have with the absent grandmother and avoid turning it into an excuse to deceive, and accuse, and ultimately to abandon the people she loves the most?

I invite you to read my companion novel Passport Control where you will meet Miriam Gil and her father again and find out. Meantime, I would love to hear your thoughts.

Recommended:

READING ISRAEL BOOK CLUB

Get Started Reading Israel today!

About the Author