The Spirit of Community: Parashat Vayakhel

By Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, Z"L

What do you do when your people has just made a golden calf, run riot and lost its sense of ethical and spiritual direction? How do you restore moral order – not just then in the days of Moses, but even now? The answer lies in the first lines of today’s parsha, Vayakhel.

The episode of the Golden Calf began with these words, “When the people saw that Moses was so long in coming down from the mountain, they gathered themselves [vayikahel] around Aaron…” (Ex. 32:1) At the beginning of this week’s parsha, having won God’s forgiveness and brought down a second set of tablets, Moses began the work of rededicating the people, “Moses assembled [vayakhel] the entire Israelite congregation…” (Ex. 35:1) Moses performs a tikkun, a mending of the past, namely the sin of the Golden Calf. He did this in the obvious sense of restoring order. When Moses came down the mountain and saw the calf, the Torah says the people were peruah, meaning “wild, disorderly, chaotic, unruly, tumultuous.” He “saw that the people were running wild and that Aaron had let them get out of control and so become a laughingstock to their enemies.” They were not a community but a crowd.

The Torah signals this by using essentially the same word at the beginning of both episodes. It eventually became a key word in Jewish spirituality, k-h-l, “to gather, assemble, congregate.” From it we get the words kahal and kehillah, meaning “community.” Far from being merely an ancient concern, it remains at the heart of our humanity.

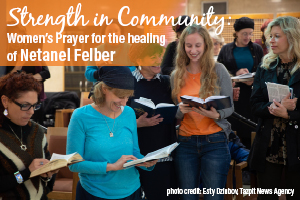

They had sinned as a community. Now they were about to be reconstituted as a community. Jewish spirituality is first and foremost a communal spirituality. Moses then directs their attention to the two great centers of community in Judaism: one in space - the Mishkan, the Tabernacle, that led eventually to the Temple and later to the synagogue, and the other in time - Shabbat. Why these two commands rather than any others? Because Shabbat and the mishkan are the two most powerful ways of building community. These are where kehillah lives most powerfully; on Shabbat when we lay aside our private devices and desires and come together as a community, and the synagogue, where community has its home.

Pioneers building Jewish settlements in Eretz Yisrael, 1920s

The best way of turning a diverse, disconnected group into a team is to get them to build something together. That is what Moses understood and did. He knew that if you want to build a team, create a team that builds. Team-building, even after a disaster like the golden calf, is neither a mystery nor a miracle. It is done by setting the group a task, one that speaks to their passions and one no subsection of the group can achieve alone. It must be constructive. Every member of the group must be able to make a unique contribution and then feel that it has been valued. Each must be able to say, with pride: I helped make this.

Similarly, the best way of strengthening relationships is to set aside dedicated time when we focus not on the pursuit of individual self interest but on the things we share, by praying together, studying Torah together, and celebrating together. Shabbat and the mishkan were the two great community-building experiences of the Israelites in the desert.

Judaism attaches immense significance to the individual. Every life is like a universe. Each one of us, though we are all in God’s image, is different, therefore unique and irreplaceable. Yet the first time the words “not good” appear in the Torah are in the verse, “It is not good for man to be alone.” (Gen. 2:18) Much of Judaism is about the shape and structure of our togetherness. It values the individual but does not endorse individualism.

Community, however, is essential to the spiritual life. Our holiest prayers require a minyan. When we celebrate or mourn we do so as a community. Even when we confess, we do so together. Maimonides rules that, “One who separates himself from the community, even if he does not commit a transgression but merely holds himself aloof from the congregation of Israel, does not fulfill the commandments together with his people, shows himself indifferent to their distress and does not observe their fast days but goes on his own way like one of the nations who does not belong to the Jewish people — such a person has no share in the world to come.”

Ours is a religion of community. Our holiest prayers can only be said in the presence of a minyan, the minimum definition of a community. When we pray, we do so as a community. Martin Buber spoke of I-and-Thou, but Judaism is really a matter of We-and-Thou. Hence, to atone for the sin the Israelites committed as a community, Moses sought to consecrate community in time and place.

This has become one of the fundamental differences between tradition and the contemporary culture of the West. There is a loss of “social capital,” those ties that bind us together in shared responsibility for the common good. The two themes of Vayakhel – Shabbat and the Mishkan, today the synagogue – remain powerfully contemporary as an example of Israel as a nation - and in truth, of Israel as a culture and society as well. They are antidotes to the attenuation of community. They help restore “the subtle ties that bind human beings to one another.” They reconnect us to community.

Religion creates community, community creates altruism, and altruism turns us away from self and toward the common good. There is something about the tenor of relationships within a community that makes it the best tutorial in citizenship and good neighborliness.

Consider Shabbat. The difference between holidays or vacations, and holy days is that a vacation is individualist (or familial) in character. Everyone plans his own vacation, goes where he wants to go, does what he wants to do. Shabbat, by contrast, is essentially collective, “you, your son and daughter, your male and female servant, your ox, your donkey, your other animals, and the stranger in your gates.” It is public, shared, the property of us all.

Havdallah - photo credit: Moishe House

A vacation is a commodity. We buy it. Shabbat is not something we buy. It is available to each on the same terms, “enjoined for everyone, enjoyed by everyone.” We take vacations as individuals or families. We celebrate Shabbat as a community.

Something similar is true about the synagogue – the Jewish institution, unique in its day, that was eventually adopted by Christianity and Islam in the form of the church and mosque. By placing community at the heart of the religious life and by giving it a home in space and time – the synagogue and Shabbat – Moses was showing the power of community for good, as the episode of the Golden Calf had shown its power for bad. Jewish spirituality is for the most part profoundly communal. Hence my definition of Jewish faith – the redemption of our solitude.

Vayakhel is thus no ordinary episode in the history of Israel. It marks the essential insight to emerge from the crisis of the golden calf. We find God in community. We develop virtue, strength of character, and a commitment to the common good in community. Community is local. It is society with a human face. It is not government. It is not the people we pay to look after the welfare of others. It is the work we do ourselves, together. Community is the antidote to individualism on the one hand and over-reliance on the state on the other. And it began in our parsha, when Moses turned an unruly mob into a kehillah, a community - Am Yisrael.

CELEBRATE YOUR PRIDE AS A MEMBER OF THE GLOBAL JEWISH COMMUNITY OF VIRTUAL CITIZENS OF ISRAEL TODAY

FOOD FOR THOUGHT:

- What does community mean to you?

- What community do you most feel a part of?

- Is community only a physical entity, or can a virtual community also provide the strength that Rabbi Sacks highlights?

- How can the Jewish people feel a sense of belonging as a community in spite of the differences that divide us - religious, political, ideological, geographical, cultural?

- How does being a Virtual Citizen of Israel help you feel the sense of belonging with your fellow Jews around the world?

- What would you do to strengthen the engagement of the Virtual Citizen of Israel global community?

Recommended for you:

STAY CONNECTED NO MATTER WHERE YOU LIVE

Share your love of Israel as a Virtual Citizen of Israel today!

About the Author